Of course what I’m really talking about is markets. And access. And heterarchies. And manipulations/contortions…

Access to the Baltic Sea from the Atlantic is restricted to three primary passages (prior to the Kiel Canal completed by Kaiser Wilhelm in 1895): the Lillebelt, the Storebelt, and the Øresund.

Travelling by boat from the town of Skagen on the northern end of the Jutland penninsula to the Baltic differs as follows:

| Passage | Distance | Time | Fuel Cost |

| Øresund | 362 km | 19.5 hours | $487.45 |

| Storebelt | 537 km | 29 hours | $724.39 |

| Lillebelt | 604 km | 32.6 hours | $814.31 |

(Assuming modern day fuel prices in Europe for diesel, averaged across Scandinavia, and a speed of 10 nautical miles per hour, burning roughly 15-20 gallons of fuel per engine per hour.)

Travelling via the Øresund is roughly 40% cheaper than the Lillebelt, 33% cheaper than the Storebelt. Additionally, both Belts are relatively shallow. Not to mention you would be wending your way throughout the island homes of former Vikings (the etymology of the word itself is probably derived from Old Norse: “creek, inlet, bay” & Old English: “settlement, camp,” although it came to mean piracy – Old Norse: fara í viking means “to go on a viking,” “to go about pirating”).

A fort existed at Helsingør (derived from hals, “neck, narrow strait”) as early as 1200. King Eric of Pomerania institued the “Sound Dues”(Øresundstolden) in 1429. Every ship passing through had to pay, and that money went straight to the Danish royal family. In 1567 the clever King Frederick II changed the tax to 2% of the cargo value (which tripled the income to the throne). Shrewd Frederick reserved the right to purchase the entire cargo at cost, which tended to keep captains from undervaluing their merchandise.

All that money went into constructing the Kronborg castle, and to funding the King’s militaries to patrol for pirates and guarantee safe passage. Restrict access (output). Inflate prices. The Sound Dues account for two-thirds of Denmark’s state income in the 16th and 17th Centuries.

After the age of the Vikings, the Hanseatic League came to dominate trade and markets across northern Europe for over 400 years. These merchants spread all around the coasts of the Baltic, stretching to Brugge and London in the west.

The Hansa had no flag. No seal. No king. No real laws or regulations. But it acted en masse like a cartel. Hansa towns (mostly ports) dealt in bulk. Grain from the east. Herring and cod from the seas and oceans. Timber, pitch and tar from the north. Cloth from Flanders and England. All items with low profit margins. So to make money, they had to establish a monopoly on shipping. Control of the flow of goods, and therefore price.

A fascinating economic analysis of the “Hansa” inspired by Network Theory models posits:

Compared to hierarchical forms of enterprise, a network features a horizontal, little formalized and constantly changing structure. It is often a self-organizing form of cooperation and develops around one or more hubs or nodes, be it in the sense of an ego-network or a heterarchical network. In the first case, the actor is at the center of the anlysis, whereas the second case resembles a neural network with multiple nodes of varying density. Unlike the market, the relationship between the actors are not solely regulated according to competition and price or supply and demand. Instead, the reciprocal transactions are determined by a web of social factors such as obligations, trust, solidarity and reciprocity.

The cohesion of the network is thus produced less through formal rules and contracts than through the presence of a common culture and common goals.

Control of a resource or a product – such as a shipping channel, or a shipping network, or a life-saving shot of epinephrine to counter anaphylactic shock – enables a means of manipulating normal price elasticity.

Control or dominance of “information shipping lanes” resulted in the massive increase in marketing departments in the 20th Century; a trend that the “information superhighway” invented by Al Gore only exacerbated. The explosion of information repositories has experienced an unusual and mostly unanticipated consolidation to relatively few platforms of social media, many of which serve as the primary source of news content consumed by users.

Mylan’s “EpiPen” is an interesting example of a product whose history demonstrates the kinds of information market control efforts undertaken by the holder(s) of its (copy)rights.

In 2014, the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development updated their 2003 estimates for the cost of developing a pharmaceutical product to market approval (the FDA bottleneck) to: 10 years development, $2.9B investment. In the USA our regulatory agency is responsible for:

… protecting the public health by ensuring the safety, efficacy, and security of human and veterinary drugs, biological products, and medical devices; and by ensuring the safety of our nation’s food supply, cosmetics, and products that emit radiation.

(Whether you believe that the role of a government is to attend to the needs of the people, as in a constitution that is “of,” “by,” and “for the people,” is up to you. But governments interfere with markets: that’s unquestionable.)

A feature of this market is an approval bottleneck. A feature of 21st Century markets in particular is the (social) “network effects” (also called network externality or demand-side economies of scale: the effect that one user of a good or service has on the value of that product to other people). Combine the two and you have a unique regulatory & policy framework that, when leveraged cleverly, tips markets to a particular winner.

Exempli gratia: Mylan acquired the rights to the EpiPen in 2007 when it produced $200M in annual sales and controlled 90% of the market. The company spearheaded initiatives to “raise public awareness” (to increase demand) by enabling patient sponsors and lobbying the federal government to mandate that epinephrine autoinjector devices are stocked in public schools (and also, ideally, in restaurants, hotels, and any other public spaces (much like defibrilators have been – Mylan hired the same marketing consultants who generated this advocacy). With few competitors approved through the FDA (bottleneck) process, essentially a de facto market dominator, you now create a de jure market winner: mandated public institutions, compelled by law, will pass on the (C.Y.A.) responsibility to the parents of at-risk children. (Id est: “you must buy this epinephrine auto-injector product, and no other” – many parents face this prerequisite condition, or their kids don’t go to school.)

Result: 2007, sales are $200M and 90% market dominance. In 2015, sales are $1.5B and still 90% market dominance. As a single product it accounts for about 40% of Mylan’s profit. The device delivers about $1 worth of drug, and costs around $35 to manufacture.

But I’m not trying to paint Mylan as a company motivated by nefarious intent: they are a for-profit entity who has invested in creating demand (manipulating the market) by the means available to them (and for which they are facing regulatory and public backlash).

This is not a free market. As the examples of the Sound Dues and the Hanseatic League modus operandi demonstrate, rarely are markets ever truly free. And conditions for a “perfect market” are unobtainable.

Neither am I apologizing for Mylan’s business model. I’m rather fascinated by accumulating information: much of this tends to bolster my belief that certain products are not best served by the market structures we create for them. Particularly those where we weigh the balance as such:

“Lives are at stake” vs. “Lifestyles are at stake.”

The Sound Dues ended in 1857. The Copenhagen Convention which turned the three “belts” into “international waterways” (free to all commercial and military ships) was precipitated by a US merchant vessel refusing to pay. They were backed by the declaration from the US government.

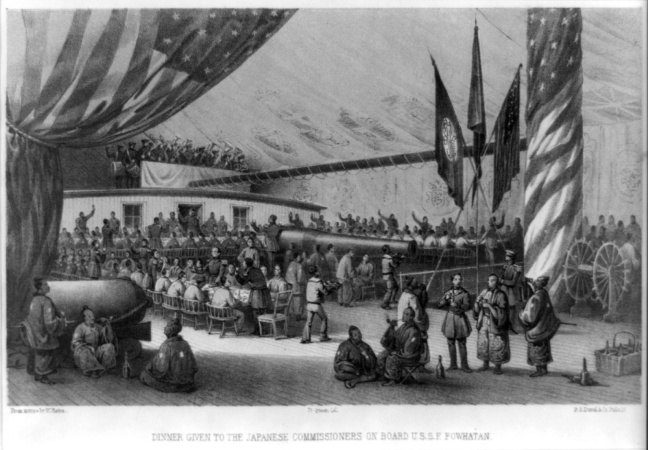

In 1853 the US Navy, ordered by President Fillmore, sailed four gunships into Uraga Bay outside Tokyo and threatened to open fire. Their demands: to open Japanese ports to American trade.

These aren’t “invisible hands.”

If I remember my Norse mythology, this is Bure (or Bùri) and Ymur. (My saga transliterated him as “Bure,” which I read sometime in junior high school and apparently has been obviated in the age of wikipedia to a more proper translated entity: like diphthongs, translations glide over time. There’s something about when your childhood memories get corrected by collective wisdom…)

If I remember my Norse mythology, this is Bure (or Bùri) and Ymur. (My saga transliterated him as “Bure,” which I read sometime in junior high school and apparently has been obviated in the age of wikipedia to a more proper translated entity: like diphthongs, translations glide over time. There’s something about when your childhood memories get corrected by collective wisdom…)